The Vigenère cipher

The Vigenère cipher is an evolution of the Caesar cipher that introduces the concept of a key.

A Bit of History

Contrary to what its name suggests, the Vigenère cipher seems to have been invented by Giovan Battista Bellaso, an Italian cryptographer from the 16th century.

Nevertheless, it is the Vigenère cipher that endured, not Bellaso’s.

Blaise de Vigenère introduced his cipher 20 years after Bellaso, with some improvements.

This encryption method began to be called the Vigenère cipher from the 19th century onwards, without regard to Bellaso. Moreover, Bellaso was quickly forgotten in favor of Porta.

Lots of names. Ah, history!

Of course, this cipher is not secure and was broken as early as the 19th century.

Note: This post was translated from french with the help of AI. The original post was written with the knowledge of a younger me.

The Key Instead of the Shift

The Vigenère cipher introduced a major innovation compared to the Caesar cipher: the concept of a key.

This difference classifies this cipher as polyalphabetic rather than monoalphabetic. It is no longer “one plaintext letter gives one and only one ciphertext letter,” but a plaintext letter can produce two different ciphertext letters, and a ciphertext letter can come from two different plaintext letters.

Therefore, multiple substitution alphabets are used (different letter shifts within the same message), unlike the Caesar cipher. Hence the term “polyalphabetic.”

The substitution rules (how you switch from one alphabet to another) are given by the letters of the key and a substitution table.

Don’t quite get it? We will illustrate this with examples in the following chapters, no worries.

Also, another article will cover the classification of ciphers.

The Cipher Itself

Let’s get to the heart of the matter. There are two ways to represent the classic Vigenère cipher (with variants being another story).

Table Representation

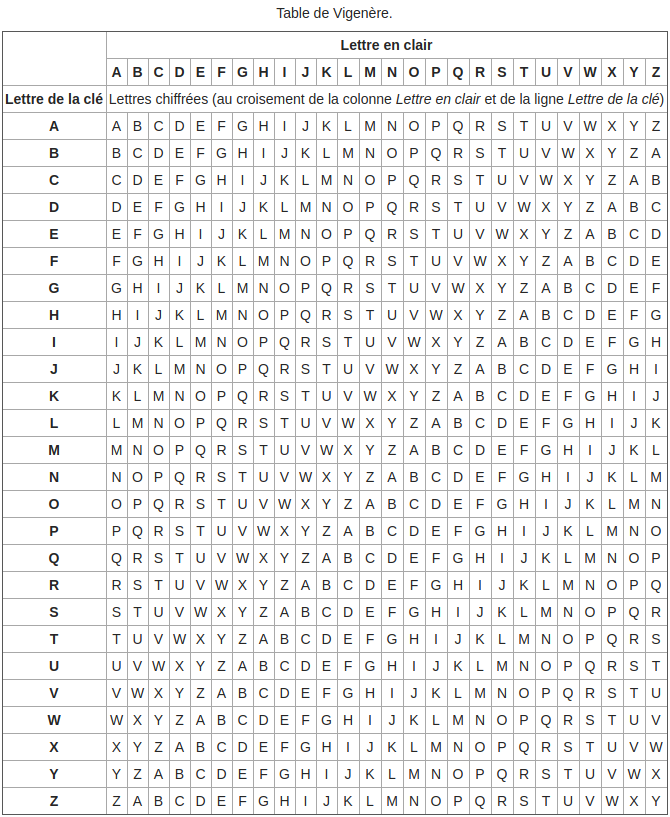

For the table representation, we need a table (yes, really), or rather a substitution matrix. Here it is:

Vigenère Table

Columns show the plaintext message, rows show the keyIt may look dense but it’s not so complicated. If you look at the rows, you see the Latin alphabet shifted by one letter per row. Similarly for the columns.

The cipher works by taking the letter at the intersection of the plaintext letter (columns) and the key letter (rows). That intersection letter is the ciphertext letter.

Example:

Encryption

Take the message: “J’ai plaqué mon chêne” (excerpt from “Auprès de mon arbre” by Georges Brassens)

And the key: “Una mattina” (excerpt from “Bella Ciao”)

Look at the intersection of each letter:

Column “J” and row “U” give “D”, column “a” (ignoring the apostrophe for now) and row “n” give “n”, column “i” and row “a” give “i”, etc.

If the message is longer than the key, repeat the key. Consider “ê” and “é” as “e”.

We get: “D ni bltjcr mia ctegx”

Decryption

For decryption, for each row corresponding to the key letter, find where the ciphertext letter is located and take the letter at the top of that column, which is the plaintext letter.

So, taking the key: “Una mattina” And the ciphertext: “D ni bltjcr mia ctegx”

In row “U”, letter “D” is at the 10th position, so column “J”, in row “n”, letter “n” is at the 1st position, column “a”, etc.

We recover: “J ai plaque mon chene”

Congruence Representation

The second representation is mathematical: congruence. If you don’t know this word, check this article.

To use congruence, substitute letters with numbers using the rule:

A=0, B=1, C=2, D=3, E=4, F=5, G=6, H=7, I=8, J=9, K=10, L=11, M=12, N=13, O=14, P=15, Q=16, R=17, S=18, T=19, U=20, V=21, W=22, X=23, Y=24, Z=25

To encrypt, add the key to the message. To decrypt, subtract the key from the message.

Example:

Encryption

Take the message: “J’ai plaqué mon chêne” And the key: “Una mattina”

Align the message and key (removing apostrophes and accents) and repeat the key to cover the message:

"J ai plaque mon chene"

+

"Una mattina Una matti"

=

9

+

20

=

29

There’s no letter with value 29 (max is 25), so we use congruence modulo 26 (numbers 0 to 25).

Thus,

$$ 29 \equiv 29-26 \pmod{26} \equiv 3 \pmod{26} = D $$

We continue calculating:

"J ai plaque mon chene"

+

"Una mattina Una matti"

=

9

+

20

=

29

≡

3 mod(26)

=

D

And so on. We get the ciphertext: “D ni bltjcr mia ctegx”

Decryption

To decrypt, subtract the key from the ciphertext, again using congruence.

"D ni bltjcr mia ctegx"

-

"Una mattina Una matti"

=

3

-

20

=

-17

≡

-17+26 mod(26)

≡

9 mod(26)

=

J

Step by step, we return to: “J ai plaque mon chene”

Variants

The Vigenère cipher has known many variations. Here are a few:

The Bellaso Precursor

Before Vigenère, there was Bellaso. But the poor man was overshadowed by another Italian, better known in his time, Giovanni Della Porta, and later by Vigenère. So sometimes it’s called the Porta/Bellaso cipher.

This cipher uses the following table:

| Key | Substitution |

|---|---|

| AB | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z | |

| CD | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| Z N O P Q R S T U V W X Y | |

| EF | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| Y Z N O P Q R S T U V W X | |

| GH | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| X Y Z N O P Q R S T U V W | |

| IJ | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| W X Y Z N O P Q R S T U V | |

| KL | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| V W X Y Z N O P Q R S T U | |

| MN | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| U V W X Y Z N O P Q R S T | |

| OP | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| T U V W X Y Z N O P Q R S | |

| QR | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| S T U V W X Y Z N O P Q R | |

| ST | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| R S T U V W X Y Z N O P Q | |

| UV | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| Q R S T U V W X Y Z N O P | |

| WX | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| P Q R S T U V W X Y Z N O | |

| YZ | A B C D E F G H I J K L M |

| O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z N |

The left column contains the key letter, and the right column contains the substitution.

A quick example to show how it works:

Encryption

Take the message: “Trois Anneaux pour les Rois Elfes” (excerpt from Tolkien’s “The Lord of the Rings” in french)

With the key: “La République Galactique” (excerpt from Lucas’s “Star Wars” in french)

The first key letter is “L”.

Look for this letter in the first column; “L” is in the sixth row with “K”.

The first letter of the message is “T”. Find “T” in the second column on the sixth row.

You see that “T” is below “L” (in the two lines present in each second column row), so the ciphertext letter is “L”.

Next, the second key letter is “a” (to make sure you’re following).

It is in the first row of the first column. The second plaintext letter is “r”.

In the second column of the first row, “r” is below “e”, so the ciphertext letter is “e”.

Then:

- “R”: 9th row: “o” becomes “j”,

- “e”: 3rd row: “i” becomes “t” (“i” is above “t”),

- etc.

The ciphertext is: “Lejtm qafnsem fbme xvb ijyh zyxpm”

Decryption

Use the key to find the row and match. So:

With the key: “La République Galactique” And ciphertext: “Lejtm qafnsem fbme xvb ijyh zyxpm”

- “L”: 6th row: “L” becomes “T”,

- “a”: 1st row: “e” becomes “r”,

- etc.

You recover the message: “Trois Anneaux pour les Rois Elfes”

Beaufort

We’ll quickly cover this and the next variant. The only difference from Vigenère is that instead of adding the key to the message to encrypt, you subtract the message from the key.

So to decrypt, subtract the ciphertext from the key:

Key – Message = Ciphertext ⇒ Message = Key – Ciphertext

Of course, this is in the congruence representation.

German Variant of Beaufort

For this variant, it’s the opposite. Subtract the key from the message to encrypt.

To decrypt, add the ciphertext to the key:

Message – Key = Ciphertext ⇒ Message = Key + Ciphertext

Disordered Alphabet

You can shuffle the letters of the alphabet. If both correspondents have the same table, the system works.

Of course, each letter must appear only once per column and row.

Also, all letters must appear in every column and row.

For example, consider these values:

C=0, E=1, A=2, Z=3, B=4, D=5, F=6, G=7, H=8, I=9, J=10, K=11, L=12, M=13, N=14, O=15, P=16, Q=17, R=18, S=19, U=20, T=21, V=22, W=23, X=24, Y=25

Expanded or Different Alphabet

We worked with a 26-letter Latin alphabet but nothing stops you from expanding it to include extra symbols or using a different alphabet.

For example:

A=0, B=1, C=2, D=3, E=4, F=5, G=6, H=7, I=8, J=9, K=10, L=11, M=12, N=13, O=14, P=15, Q=16, R=17, S=18, T=19, U=20, V=21, W=22, X=23, Y=24, Z=25,!=26,?=27

In this case, we have modulo 28 instead of 26.

Bellaso Variants

We used Bellaso’s original table but nothing prevents modifying it.

You could have three letters in the first column instead of two and reduce the number of rows accordingly.

Or have a different number of letters per row.

Or change the alphabet substitutions in the second column.

The only requirement is that your alphabet’s number of letters/symbols is even so each symbol has a match in the second column.

Weaknesses

Frequency Analysis Attack

As mentioned in the historical preamble, this cipher and its variants were broken in the 19th century.

It suffers from the same weakness, though much more resilient, as the Caesar cipher.

Languages do not use letters with the same frequencies. For example, in French, the letter “e” is much more frequent than others.

An attacker can exploit these frequency differences to guess the message or the key.

But unlike Caesar’s cipher, there is a preliminary step.

The attacker must first try to guess the length of the key. This allows segmenting the ciphertext into equal-length segments.

To do this, they look for patterns in the ciphertext — groups of three letters or more that appear regularly.

Languages also have common patterns: for example, “les” appears frequently in French.

It’s more likely the same part of the key falls on the same plaintext pattern, encrypting it the same way, than by pure chance.

By spotting these patterns, the attacker estimates the key length and can segment the ciphertext.

Each plaintext letter in a segment is encrypted by the same key letter, allowing frequency analysis.

This might seem obscure or confusing. Don’t worry, a future article will clarify this with examples.

The Vigenère cipher is halfway between the Caesar cipher, from which it takes the substitution rule, and the one-time pad, which is the perfect algorithm, appearing only at the beginning of the 20th century.